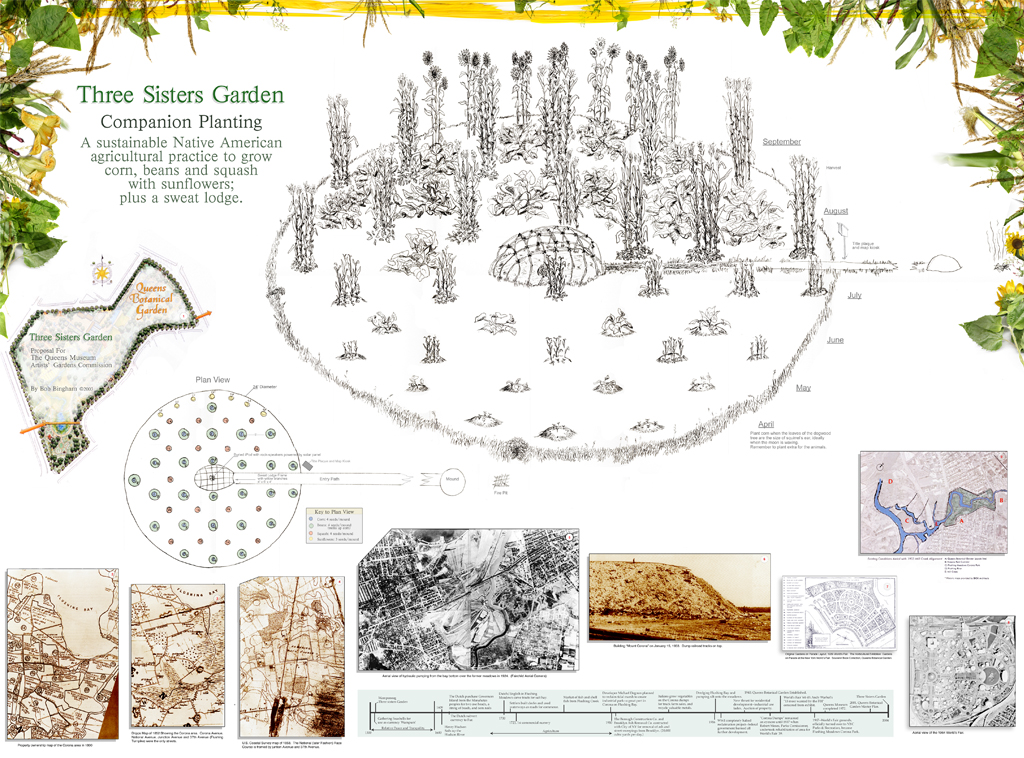

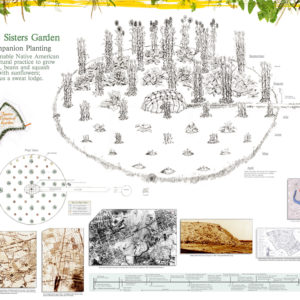

Three Sisters Garden – Companion Planting is a proposal to develop a garden based on the sustainable Native American agricultural practice of growing corn, beans and squash together with sunflowers. This proposal was created for Flushing Meadows Corona Park and took the form of a map outlining the rich history of the site after I visited as a finalist for The Queens Museum Artists’’ Gardens Commission.

Queens has the reputation of being the most diverse city in the world and the main criteria for the garden commission was to address the surrounding users of the park. Unfortunately the original users were dispossessed many moons ago. So this garden was conceived to commemorate their presence and to remind us all of their unique sustainable agricultural practice into the fabric of the Botanical Garden. Besides having local Native Americans plant, raise and harvest the crops, the garden would represent a contemporary version of traditional agricultural practice and serve to educate others about traditions and myths. Designed around a central sweat lodge frame to entice viewers into the nterior of the garden, an audio system buried in the ground would emanate Native American stories.

More information:

- Scouting Expedition to Visit the Queens

- Queens Botanical Garden Phase I Master Plan Design Concepts

- The Audio Component

- Native American Stories

- The Sweat Lodge

- Installation Site Concerns

- Materials and Maintenance Concerns

- Educational Programming

- Consultants

- Financial Resources

- Project Budget

- Installation Timeline

- Credits

3 Sisters Garden: Scouting Expedition to Visit the Queens Botanical Garden (Bigwitz)

Upon receiving word in Pittsburgh that we were finalists for the Queens Museum Artists’ Garden Commission we prepared in haste to send a scouting expedition to New York. Before sending my trusted scout Bobby Bigwitz to explore the region and visit Flushing Meadows Corona Park, he researched the area with a keen eye on the lookout for ‘a sense of place’, based on historic and contemporary culture and site conditions. I conversed on the phone and the internet to establish a few connections with people knowledgeable about the site. After initial conversations about growing green roof possibilities and the news of a serious movement towards sustainability and a progressive program to celebrate water at the Queens Botanical Garden (QBG), meetings were confirmed with museum curators, directors of the botanical garden and the parks department. I also located a variety of former art scouts living in Brooklyn and Queens to assist in the arrival of the expedition party and to prepare them for research tasks in their areas of specialization with the agreement that if the expedition was successful they may join the garden project.

As fate would have it, upon arrival to the park by car Bigwitz was unable to negotiate traffic in order to follow directions to the Queens Museum. Initially lost, then with the aid of a compass he saw signs that directed him to the Queens Botanical Garden (QBG), he parked the car and entered a side entrance with all his research and documentation tools. Video camera ready he was not prepared when immediately framing several hundred people performing tia chi led by a group of a dozen women in traditional Chinese costumes dancing with fans. In another area he witnessed a group of Japanese people ritualistically moving to the sound emanating from a boom box.

His notes report the feeling of being in another world, an oasis in the most culturally diverse city in the world. He acquired a map and an earful from a knowledgeable older woman at the info desk, then he walked through the QBG toward the Queens museum for a 10 a.m. meeting. Passing through the formal zones designated by signage and a wedding party, Bigwitz reported that his “where do we fit in here” antenna were up. Finally leaving a grove out into the open space he came to a fork in the road, a shift occurred, something about choice, something about tall grass, a prairie left to its own devices, its natural process.

He just stood there, stared, felt the wind and the sun, turned around slowly 360 degrees, tried to identify trees, noticed the placement of the garbage cans and visually followed the paths from the fork in the road. Checked the map, checked the time, figured he had to move on. He took a few photographs, again felt the wind, the sun and heard the sound of traffic that increased as he approached the pedestrian bridge. This would be the place he always came back to-by choice.

Marching briskly into the park he reports an odd sense of lifelessness, sure it is early, but where are all the people he asked himself. Traveling through the park, he noted large man-made lakes and empty concrete, fountain basins left over from World’s Fairs in 1939, 1964. There is no shortage of trash. The main activity was soccer. The formality became clear again growing closer to the museum and the giant globe filled his sight. Bigwitz reported an informative meeting at the museum coupled with a driving tour around the perimeter of the park. Bigwitz observed the overwhelming numbers of vehicles on enormous numbers of highways surrounding and bisecting the park. There are few rules spelled out, the whole park is open territory except the festival area where during summer months hundreds, thousands of people gather to celebrate their nationalities. After a Pakistani lunch and detailed notations of other interesting components in the QBG, Bigwitz outlined an extremely informative meeting about the history of the site as an ‘ash dump’ that buried Mill Creek and how through a long master planning process the future plans for the QBG are to symbolically represent the buried stream and celebrate water in every possible manner. Bigwitz procured a copy of this master plan document along with a history book of Corona as key artifacts for garden speculation. (see images on front, timeline and design principles listed below).

Bigwitz toured the park on foot, bicycle and car for two beautiful late June days. The second day Bigwitz recorded numerous observations including a later afternoon in the park with an increased number of users playing soccer, bathing in the now water full fountains, and noting that hundreds of people were joyously frolicking in the global fountain-pool. It was the most diverse group of people he had ever witnessed in the same place sharing a like activity; truly universal. Bigwitz recorded this event photographically and on video. He also documented potential garden sites near the museum. Next he reported a variety of observations after visiting the Museum, having heard a lot about the three-dimensional model of NYC he planned to visit and study for site preparation, however he was distracted by the World’s Fairs exhibit. One of the very first plaques caught his attention, it was about:

In !993, Chief Oceola Townsend, Matinnecock Tribe, filed a claim against the U.S. government for return of 1300 acres in Flushing, Douglastown, Fort Washington, Huntington NY including Flushing Meadows Corona Park. He claimed since the seventeenth century, negotiations were unlawful. The Matinnecock’s do not have a reservation, thus they are not recognized by the federal or state governments.

The next one that caught his attention was about Andy Warhol who was censored in the 1964 Fair having huge print/paintings of the 13 most wanted by the FBI, however the Palestinian pavilion that many complained about was not censored. He noted that the Japanese pavilion from 1939 donated as a permanent gift was vandalized beyond repair in 1942. Leaving the Queens Museum he returned for one more site visit to the pedestrian bridge, but the gates were locked. So he recorded observations from a new perspective, from outside the fence.

Back in the ‘Burgh

At the ranch, we entered that place of inspiration, the sweat lodge. Sweating, grappling with the elements: fire, water, air, earth; we dug deep into history. We were reminded that history does not include Native Americans, much.

This led to unanswered questions:

- If the Dutch paid the Manahatas peoples two ax heads a string of beads and some nails for Governors Island, what amount was paid by the Dutch and/or Swedish for the Flushing Meadows?

- How to design an art garden on a small budget?

- How to include a diverse population of users: Asian, Central American, Middle Eastern?

- How to artfully engage viewers and users to participate in an educational experience?

We kept returning to how sustainable the Native American culture was/is. Initially Bigwitz researched ‘water rites’ of Native American culture and myths that included stories of the sweat lodge so we began growing an idea around the rituals related to stones and water, this led to the combination of a typical sweat modeled after the Wamponoag tribe combined with a Three Sisters Garden Companion Planting which seemed to fit all categories of the original design principles for the QBG.

While studying maps of the early settlement and development of Queens through history (see images 2,3,4 reverse side) we realized that a map presentation would contribute to the information sharing/reading of the art garden as well as serve education purposes and the mission of the QBG. A significant component is to include oral histories of Native Americans to counteract the problem of why written history does not often exist; a way to sustain Native American history.